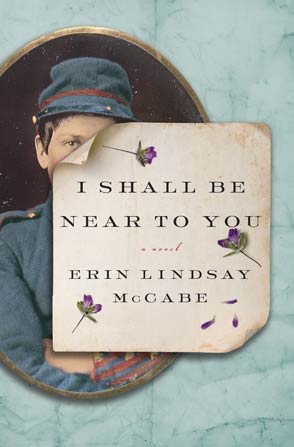

Watch Erin read from Chapter 3 of I Shall Be Near To You here

I take the sturdy shears out from the bottom of my hope chest. I carry them through the hall to the kitchen hearth and I don’t stop to think; I sit in front of that woodstove, still throwing out heat from the morning’s cooking, and plait my hair into one thick braid hanging down my back. Then I push those shears to the base of my braid and force down, using both hands to make those scissors saw my hair bit by bit, cutting it all off. It falls to the floor with a heavy thump, a light brown snake coiled behind me.

I stare at it there and Betsy’s voice is in my head saying, ‘Why you got such pretty hair? All wasted on someone who don’t care none about it?’

Then I feel Jeremiah running his fingers through my hair, but I’ve got to stop that. I snatch that braid up, the top thick and splayed, the bottom curled to a tip, and fling it into the cinders. It almost chokes out the fire, but I breathe on it and use fresh kindling from the box to poke it down until the flames lick at the braid, filling the room with its awful smell.

In our bedroom, there’s a pair of Jeremiah’s old trousers, ones he’s got the hems frayed and worn down on. I step into them, trying not to look at Eli’s fingerprints pressed into my thigh, turning up the legs to fit. I fold my apron and my mended dress and the petticoat and lay them in my chest, where they will be waiting when we come back. Those sheets Betsy worked at hemming so carefully tear easily into long strips. When I have rolled up all the strips but one, I hold it against my bosom with one hand, getting it under my arm and then wrapping it tight around myself. It’s hard at first but I keep pulling it tight and then it’s working. I cover myself with Jeremiah’s old shirt and roll the sleeves before getting Jeremiah’s straw hat from the hook by the door. In the looking glass that used to be Mama’s I make my face look like stone, with tight lips and my jaw pushed out. I tip the mirror down to see the shirt and trousers, how they fit loose enough to hide everything. I could do it so easy, earn a soldier’s pay instead of just a nurse’s or a laundress’s and stay with Jeremiah for as long as this war drags on.

He will be happy to see me, his face lighting up like our wedding day, all the more handsome in his uniform. He will tell me he is sorry for going like he did, that he never should have done it, how it was the boys that made him leave, that he was wrong to tell me I couldn’t come along.

Only maybe it won’t be like that. Once Jeremiah blacked Henry’s eye after school, all because Henry whispered ‘son of a whore’ after Jeremiah’s name at roll call and the whole class snickered. Jeremiah simmered for hours, the heat of his anger enough that Henry broke for the outhouse as soon as Miss Riggs’ bell tinkled.

I ain’t ever made Jeremiah mad like that. We ain’t ever argued for real. Not even once.

But I have to do it now, I have to go, because I can’t show my face to Jeremiah’s Ma with my hair like this. Jeremiah won’t care that it don’t look good, it won’t matter with a cap on, covering it. Plenty of people don’t have nice hair.

Back in my own clothes, I sit myself down to work, staying up past the moon’s rising, making neat hems on Jeremiah’s old trousers and cutting down the sleeves on two of his shirts.

I wake at dawn, my neck cricked, still sitting in the chair by the fire, the last of the hemming just a few stitches from finished.

In the kitchen I dig for a burlap sack. There is hardly a thing for me to pack. The map. Jeremiah’s letter. Flannel rags for my woman’s time, extra socks, a wool blanket rolled up tight, two boiled eggs, two thick slices of bread, and some side meat, all wrapped in cheesecloth. I wind a scarf around my neck and tug Jeremiah’s hat down over what’s left of my hair. I am just about to go through the door, when I remember the mending for Jeremiah’s Ma. I scratch out a note saying Gone Visiting and leave that with the basket on the porch. Then I lift my sack and sling the canteen across my chest and walk out under the gray sky, bracing myself for what is a day’s hard ride on horseback. I look back once at the Little House, a thin trail of smoke still drifting up from the stovepipe. I think on Papa and Mama and Betsy reading every night around the fire. Words from Preacher Bowers’ sermon come back to me, about Adam and Eve being cast out in sorrow. Only I don’t feel sad to be leaving when that place ain’t my home no more, and without Jeremiah, this place ain’t my home neither.

I don’t even make it to the church before I start thinking on the first casualty list Preacher posted on the door, back when the little boys, Tommy O’Malley, Phin Cameron, and John Lewis, were still lining up to march back and forth with Lars Nilsson yelling orders. Back before those little boys’ mamas made them quit playing soldier on Sundays.

The only good thing about that list was how it made Jeremiah get around to making things official, him coming to Papa, his hat in his hands, saying, ‘Good morning, Sir,’ and then his eyes flicking toward mine before adding, ‘I was coming to ask permission to walk Rosetta home, Sir.’

All those weeks he walked me home from school, he ain’t never asked permission.

I wish I were walking down Carlisle Road like that now, with Jeremiah crooking his elbow like he is a fine gentleman and I am a lady, feeling the heat coming off him through his cotton shirt, my steps matching his. Leaving Jeremiah’s Ma standing straight in her lace collar, her two daughters-in-law and Mrs. Snyder beside her, prying after us.

Back then the first thing he said was, ‘You look real nice in that dress,’ and when I told him, ‘It’s the same dress I always wear to church,’ he pushed me with his elbow, laughing as I staggered sideways.

‘Maybe you always look nice,’ he said.

I wonder if he’ll think that now.

At the old oak, where the path veers off from the road, I can almost see Jeremiah shuffling down the slope to the creek before me, down into the ferns, and holding out his hand, smiling at me with his head cocked to one side like it is a question or a test. I took his hand that day and ain’t ever felt anything so nice, even when our hands got to sweating.

Down by the creek, Jeremiah’s look made me get to feeling nervous, like there was something different between us, the way the air changes before a storm.

I said, ‘I want to cool off a bit,’ and undid the laces of my boots, rolled down my stockings, slipped them off.

Holding my skirt out so it wouldn’t get wet, I squished the silt between my toes, the water cool enough to almost make me forget the sweat-damp dress sticking to my back. Dipping my free hand into the creek, I skimmed it along the back of my neck. Jeremiah stood rooted.

Just to make him stop staring, I said, ‘You remember the last time we were here, just us? You remember how you said you wanted your own farm?’

‘Course,’ he said.

‘You still want that?’ I asked, standing so quiet a fingerling fish brushed up against my ankle.

‘I do,’ he said, ‘I’ve been keeping those ideas in my head. But the war—’

‘You still thinking on Nebraska?’

‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘I’ve been thinking on that. Could get a whole farm, a hundred sixty acres, for maybe two hundred dollars.’

I don’t know what made me do it but when I stepped out of the creek, I brushed against him as I headed for my shoes. He turned to watch me, that look coming back.

‘How you going to get that kind of money?’ I asked, stooping to get my things. ‘My Papa can’t pay you none.’

‘I ain’t working for your Papa for money. I’ve got other ideas.’

My cheeks got hot and I couldn’t say a thing so I washed off the dirt and leaves sticking to my feet, dunking my toes into the water before standing on one leg, trying to get that clean foot back into my shoe.

‘Here,’ Jeremiah said, walking to the edge of the water and holding out his arm. I grabbed hold to steady myself, planning on saying thank you or else asking what other ideas he has got, but those words stopped in my throat. I didn’t move as he bent closer, his arm reaching across my back, his mouth pressing to mine and it was hot and wet and my arms went right around him.

When he drew away from me, I didn’t want him to quit. My eyes opened onto his blue ones and I couldn’t remember closing them. I looked at his jaw and the stubble growing there. He bent to me again, but before his lips touched mine he said, ‘You still want that farm too?’ and I didn’t have to say yes, I just let him kiss me.

I wake under a bare-limbed tree at first light, my head resting on my pack, my blanket tucked up to my chin, my back aching from the cold or all the walking. Off in the distance there’s the rumble and creak of a wagon, and that gets me up. When it comes close, the old man sitting on the bench nods all friendly while his skinny bay horse draws him past.

I jog after that wagon until the farmer says ‘Whoa,’ milking the reins until the gelding stops.

‘’Scuse me,’ I say, my voice catching in my throat.

The old man leans a bit closer. Maybe I should have let him keep driving.

‘You heading to Herkimer?’

‘No,’ he says.

‘You know how much farther it is?’

‘More than fifteen miles, I expect,’ the man says.

It makes me want to kick rocks or throw sticks after walking so hard yesterday and I ain’t barely halfway there.

‘You mind giving me a ride?’

‘I’m only going up the road a little piece,’ he says, ‘but it’ll save you a bit of walking.’

I croak out, ‘Thank you,’ and haul myself up onto the wagon. I have only just sat when he clucks and slaps the reins on the bay’s back, making the horse lurch into the trot.

‘What’s your business in Herkimer?’ the man asks over the sound of the horse’s hooves. ‘You looking for work?’

‘I aim to enlist.’

‘Well, now!’ He turns to give me a quick look. ‘Ain’t you awful young for a soldier?’

Before I can think what to say to that, he pulls up his pant leg, showing me the long, jagged scar running from his knee down into his boot. ‘Got this in Mexico. I was luckier than most. Got to keep the leg and never got yellow fever or the pox or none of it. Fared better than most everyone I knew, that’s for damn sure.’

When my silence gets too long he says, ‘You’re mighty brave, going it all alone.’

‘I’ve got a cousin I’m meeting.’

‘The friend I joined up with never even made it as far as Texas. The bloody flux is what got him.’ He looks me over again. ‘But you look healthy enough.’

And then he is stopping at a lane and saying, ‘I guess I can’t convince you to help unload this timber then, can I?’

‘No, Sir,’ I say, and clamber down fast.

‘My wife will have a hot supper on . . .’

‘I thank you kindly, but I’m already late getting there.’

‘Best of luck to you then. The march ahead of you ain’t nothing a good soldier can’t manage in a day. You’ll know you’re getting close when you start smelling the tannery. Damned if it don’t make me think of Texas every time . . .’

I look back the way I’ve come. Papa’s always saying there’s work enough on the farm for a dozen farmhands and how I ain’t got to be married if I didn’t want. If I’d asked, he would have sent Isaac Lewis on his way and let me be his farmhand again.

But then there is that farmer, putting his hand up to wave as he turns down the lane. I can almost see Jeremiah in him, driving home to his farm, to his wife, and the life I want.

I look up the road. All those miles between me and Jeremiah.