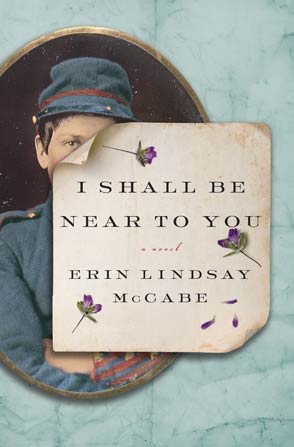

In 1998, I wandered the shadowy stacks of my university’s library, looking for a woman from the 1800s, any woman. I was searching for a primary source on which to write my final paper for U.S. Women’s History. It was there I found An Uncommon Soldier: The Civil War Letters of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, Alias Pvt. Lyons Wakeman, 153rd Regiment New York State Volunteers, 1862-1864. I learned that Rosetta was born in 1843, the oldest of nine children, that she worked as her father’s farmhand until financial trouble made her leave home at 19. Dressed as a man, she worked on a canal boat so she could send money home. It took only one boat ride up the river for her to find out that being a soldier for the Union Army paid better than any other job she could find: $13 a month plus a $152 signing bonus. She joined up, fought, died of dysentery on June 19, 1864 and was buried as a man in Louisiana. Studying the photograph of her dressed in her uniform, it’s hard to imagine her as anything other than a soldier.

I discovered Rosetta Wakeman was not an anomaly. An estimated four hundred women fought on both sides of the Civil War, many of their names lost to history. Just like Rosetta’s almost was.

I felt cheated that I had never heard of any of these women, that I’d been led to believe that women’s roles during the Civil War had been confined to the home front, that the version of history I’d been taught was so incomplete. I wanted other people to know about them too. But what I wrote was a standard college paper, and a letter to the editor of a local newspaper, both of which only a handful of people ever read. I kept thinking that if people knew about Rosetta’s feisty spirit, her colorful expressions, her turmoil over whether she would go home after the war or live alone on the prairie, they would come to love Rosetta as much as I did.

But even more, I mulled over questions Rosetta’s letters never answered. How did she conceal her identity? What did her family think of what she had done? What was she apologizing for in her letters home? What was it like, being a woman hidden among men? Did she tell anyone her real identity? Those questions fascinated me and I began imagining their answers.

***

My mom would tell me that, when she was young, before becoming a social worker and, later, a special education teacher, girls weren’t allowed to play real basketball in PE–they could only run or dribble three steps. She told me the game looked so fun when the boys played it, running up and down the full court, that after school she played real basketball with those boys, even though it wasn’t a sport “for girls.”

I grew up raising rabbits and riding my horse in Chico, California’s Bidwell Park, spending summers swimming in Butte Creek. But at sixteen I needed a job. I wanted to prove something to my 4-H woodworking instructor who told me I “hammered good—for a girl.” I wanted to build things. Really build things. My mom called Mary, the only woman she knew in construction. Mary told my mom that if I wanted to work construction, it would be hard to find anyone who would give me a chance, and if I did get hired, I would have to work harder and put up with more abuse than anyone else to prove myself. In the end, I folded. I gave up the idea and got a job at a retirement home as a server and housekeeper, listening to the old folks’ stories. But I never forgot the first time I felt like there were limitations placed on me because of my gender.

Much later, while researching the novel, I walked the battlefields of Bull Run and Antietam, tracing the steps of the 97th New York State Volunteers, imagining Rosetta marching, shouldering her rifle, firing at Confederates. I couldn’t help but admire Rosetta’s bravery even more—how she refused to be told that she couldn’t do what she wanted.

***

When I was a newlywed and working long hours during my first years as an English teacher at an underperforming high school in San Francisco’s East Bay, Rosetta receded into the background. I dabbled on other stories, poetry, essays, getting one about teaching published in The National Forum. I wrote a draft of another novel.

And then, one night, there was Rosetta’s voice. Once I heard it, I knew I had to tell her story. I had to get it right. I started down the path to earning my MFA at Saint Mary’s College of California, working on I Shall Be Near To You. Using scraps from Rosetta’s own letters, such as her account of guarding women soldiers imprisoned for “not doing according to regulation,” I began to build. I read about other women soldiers, especially Sarah Emma Edmonds and Jennie Hodgers, and I dovetailed details from their lives with events from Rosetta’s. I read soldiers’ letters, and found the story about the dance one regiment held to ease their homesickness, or the desperate Antietam nurses who used cornhusks as bandages. I checked out books about 19th Century farming.

I’ve since begun research for another historical novel based on the life of Belle Gunness, a serial killer who lured men to her home with her passionate letters, eventually murdering them and her three daughters, one of whom was adopted. I find myself wondering, as I did with Rosetta: what drove her to do it?

It was the birth of our son that made my husband and me seek a more peaceful, rural lifestyle. Now my son and I chase goats and repair fences. My husband and I buck hay by the ton for my horses. I grow pumpkins, acquire tools as tires go flat and pipes break, sew a fair seam if need be. I think of the life Rosetta left behind to be a soldier. I wonder what kind of life she really wanted.

I’m pretty sure Rosetta wasn’t trying to prove anything by being a soldier. She just knew she could do it, that she had to do it, and so she did. The accomplishments of a woman like Rosetta shouldn’t surprise us. We should know about women’s contributions just as much men’s. It shouldn’t make history that women fought in the Civil War, it should just be a part of the stories we tell.